“Today’s youth is rotten, evil, godless and lazy... it will never be able to preserve our culture.”

This quote is from an inscription on a Babylonian clay tablet from 1000 BC and referenced in Robert Greene’s 2018 book, The Laws of Human Nature.

“Today’s youth is rotten, evil, godless and lazy,” the quote reads. “It will never be what youth used to be, and it will never be able to preserve our culture.”

Our judgment of younger generations isn’t new. It’s rather old hat and cliché at this point. Throughout history, older generations have consistently believed their criticisms of the youth are unique and justified. Yet, they are merely echoing the past. They fall into the recurring illusion that younger generations are somehow inferior, convinced of their correctness while dismissing the perspectives of the youth.

Our latest iteration has a bit of a twist: it is the age of smartphones and social media. Once again, a generation of adults criticizes adolescents. This time, it’s over their technology usage and means of communication, connection, and socialization.

This leads us to one of our most profound Circle questions:

“What have you had your cellphone taken away for?”

Can any Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) or Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980) answer this? Even Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) might have a tough time. The truth is, those of us born within these timeframes can’t answer the question genuinely, and yet, these are the individuals making the “rules.”

An outcry of research is pouring in from highly renowned social psychologists, such as Jonathan Haidt. In his new book, The Anxious Generation, Haidt argues that the rise of smartphones and social media has led to a mental health crisis among young people, particularly Gen Z, by disrupting childhood development and increasing anxiety, depression, and loneliness. He attributes this to the decline of independent play and excessive screen time.

To address these issues, Haidt calls for delaying smartphone and social media use until later in adolescence, reviving free play and in-person social interactions, and reforming school policies to reduce phone dependency. The problem is that those addressing these issues do not fully understand the situation.

So, What’s the “Situation?”

Let’s take a quick detour to ensure we’re all on the same page with our human condition. Again, there is nothing new under the sun. As with all of human history, we are hardwired to connect and belong. Just look back to some of the most ancient of texts. Whether you are religious, agnostic, atheistic, or of some other persuasion, these words from Genesis 2:18 target the core of our humanity: “It is not good for the man [humans] to be alone.” This is an archetypic structure in our biology.

Judith Rich Harris, in her work on child development in The Nurture Assumption, argues that traditional views overemphasize the role of parents in shaping their children’s personalities, behaviors, and success.

Harris identifies four primary ways that children learn: (1) direct instruction, where parents or teachers explicitly teach them; (2) observational learning, where they mimic the behavior of adults; (3) conditioning, where they respond to rewards and punishments; and (4) peer socialization, where they adopt behaviors, norms, and identities from their peer groups.

While the first three — direct teaching, modeling, and reinforcement — are often assumed to be the most influential, Harris contended that they have limited long-term effects. Her most significant argument was that peer socialization is the dominant force in shaping children’s development.

Dr. Russel Barkley, a retired clinical psychologist and professor at the VCU Medical Center, states that while parents are the shepherds of their children, it will largely be the out-of-house influences that shape our life course.

From the ages of 0 to 7, humans only need to belong somewhere. Human acceptance is the driving force for young, pre-adolescent children. It is during this period of life that parents will have the most influence on their children, but that changes quickly.

Between the ages of 7 and 12, a parent’s influence drops drastically as kids begin to break away from their original pack and explore new relationships and novel sensations. After the age of 15, a parent’s influence amounts to roughly 6% of the variation in a teen’s behavior. After 21, it is zero.

Kids naturally adjust their behavior to fit into their peer groups, learning social norms, language, values, and even aspects of their personality from their friends rather than their parents. And this determines who they become as adults.

Truly, we can all understand this if we think about it. When you’re happy, when you’re sad, when you’re upset — who did you go to as a kid? Your teachers? Your parents? Other adults? Or was it your friends? Your peers? Your network of support?

Dr. Peter Wyman’s work with the Air Force’s Wingman-Connect program highlights the critical role of peer networks in shaping mental health and resilience. The program was designed to prevent destructive decisions and mental health crises by fostering tight-knit, supportive peer groups where individuals look out for one another, reinforcing adaptive, healthy social norms.

Wyman’s research found that these networks don’t just provide emotional support — they actively shape the behaviors and mindsets of those within them. If the group normalizes seeking help, expressing vulnerability, and supporting each other, those behaviors become the expectation. Conversely, if avoidance, suppression, or toxic toughness are the norm, individuals conform to those unhealthy patterns. This underscores how the most substantial influence on an individual’s well-being is the social peer network in which they are embedded.

Humans are inherently pack animals. We like to say that before the age of 10, all we care about is being accepted by our pack, our family. As we grow, we must transition from our original family unit to a new social pack — our peer group. Evolutionarily, this makes sense: we can’t reproduce within our own families, so we’re biologically wired to seek out and integrate into new groups. This process, however, is turbulent. Teenagers aren’t just rebelling for the sake of it; they’re instinctively pushing boundaries, testing group dynamics, and adopting the norms of their new “pack.”

WE Created the “Wussies”

Now that we understand the importance of these relationships we develop as humans and how they impact us, we must come onto the same page about what WE have done to the current generation.

The image embedded above is not meant to spark any debate or controversy. It is simply the image Tom Murphy was shown one day while leaving a school.

A teacher pulled him aside to whip out the image on his, 'ehem,’ phone…

After Tom had looked at it, he fired back:

“Well, who do you think created the ‘Wussies?’”

Of course, the answer was obvious: WE did.

Do you remember when your kids were just toddlers and they got a hold of your phone or tablet (or perhaps you voluntarily put it in their hands)? You probably watched (like most of us do) with amusement as they tried to figure out how it all worked. Then, as they got a little older and you got a little busier, what did you do whenever you needed to distract them or channel their energy away from ‘annoying’ you? Probably put that phone back in their hands.

Now, as they come into their teenage years, the very devices we shoved into their hands and made them addicted to, we want to take away to control or punish, all with the mindset that we’re ‘helping’ them.

Can we see the hypocrisy here?

More than that, do we understand what we have done to our children?

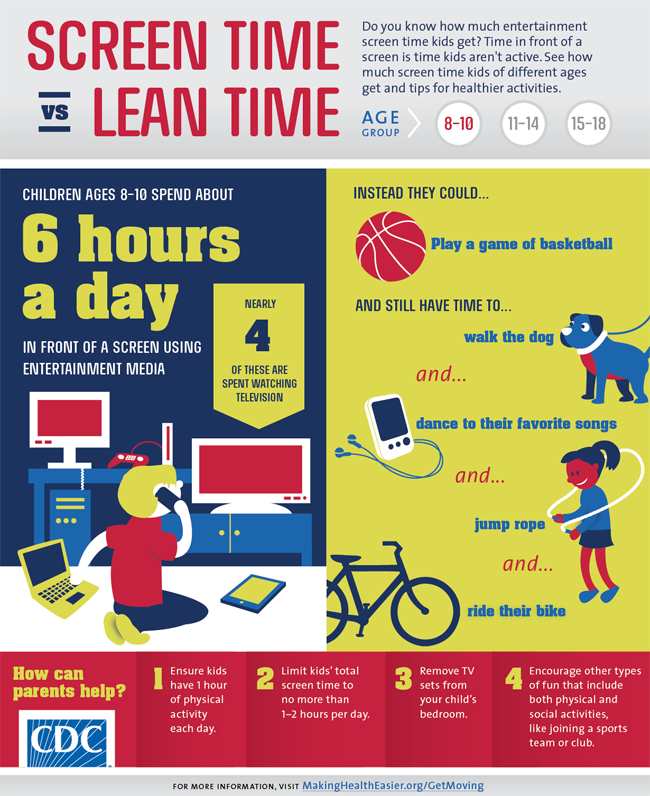

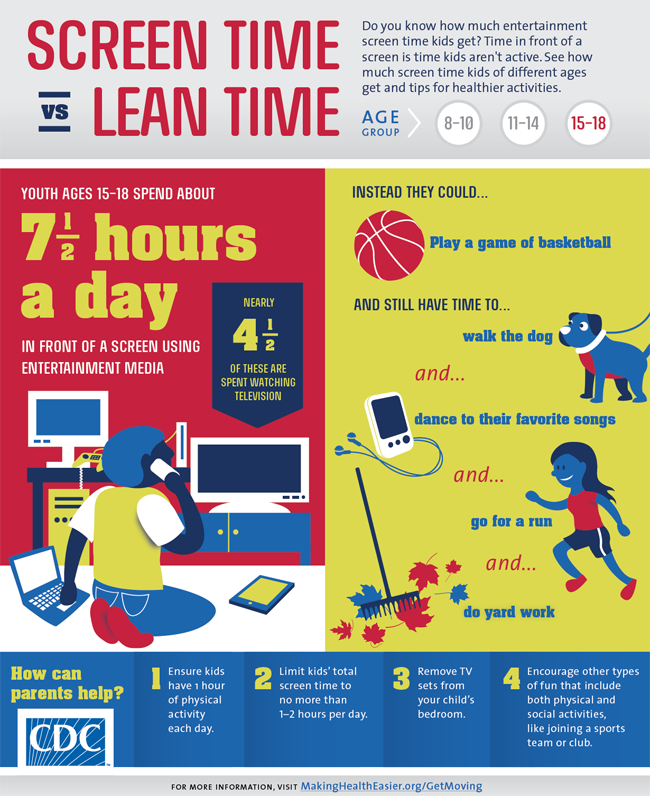

You may say, “Sure, I do! My parents sent me to my room — they separated me from my friends. They wouldn’t let me use the landline, or they took away the keys!” But in the same breath, you must also say that your brain wasn’t neurologically rewired to the degree a kid’s brain is today. Check out these facts from the CDC.

These statistics go back nearly ten years to 2016. One of the latest studies today revealed that the average teen — aged 13 to 18 — can spend up to 6½-hours on their phones JUST DURING THE SCHOOL DAY! This isn’t just a “device.” It’s part of who they are. And frankly, if we all reflect on it and exercise the self-awareness we want our children to demonstrate, we’d realize it’s part of ours.

Their Whole World’s in Their Pocket

A kid’s phone isn’t just their communication vehicle or digital entertainment system; it’s their whole world. We aren’t saying you have to like this, but when we seek to control and punish our youth — the very same hands we placed the phones into — by taking them from them, it’s not equivalent to a “go to your room” moment.

For them, it’s complete isolation from everything they know.

It’s like separating a part of themselves.

Did you know that under international law, isolating prisoners of war (beyond necessary security measures) is illegal? The Third Geneva Convention mandates humane treatment, forbidding prolonged solitary confinement or any form of inhumane isolation that leads to psychological or physical harm. While temporary segregation may be allowed for security, systematic isolation as punishment is unlawful.

Isolation is so dangerous that we don’t even do it to our enemies.

When our children make mistakes or act poorly, we often feel the need to “fix” the situation. In our lack of knowledge, we feel the only way to fix it is to take the phone away. The problem is, we’re the ones who created this whole mess.

When we take away a kid’s phone, it’s more than just imprisonment.

It’s solitary confinement and isolation.

We expect these young minds in distress to “figure it out” with the addictions we’ve inadvertently caused. We don’t know what it feels like to have our whole neurological structure built around this digital lifeline that offers them human acceptance and connection. The last thing that young minds in distress should be is removed from perhaps their only way they know how to seek or ask for support.

So, “What have you had your cellphone taken away for?”

Ask a kid this today, and most of them will tell you.

But that’s not the point of the question, nor is it to point the finger and start playing the blame game, as most of our country often seems apt to do — litigate and shove blame.

That’s not our mission. Our mission is to take action.

You can’t change the past. We can only look ahead to the future.

Our past decisions don’t define us. Our future decisions will be what people remember us for.

The point of this question is that when Tom Murphy sits in a Circle and looks out at all these faces (many young, some old, all struggling with the emotional and spiritual dogfight this world faces), he wants to help them.

In order to fix a problem, we must understand it. We must come onto a similar page or perspective built by those affected.

We’ll likely never truly understand their world of digital relationships, but at the very least, we can listen and try to understand it that much more.

It’s the chasm that our collective past has yet to conquer, and one we hope to leap in the near future. Maybe, for the first time in history, instead of condemning the next generation, we will listen. Maybe that’s how we finally break the cycle.